I can't add anything to the discussion of Thomas Piketty's masterwork, other than to say that there is a lot to be gained from reading it for economics lovers -- even if all the harshest criticisms are true.

Nevertheless, I'll note two thoughts I had that I haven't seen discussed elsewhere.

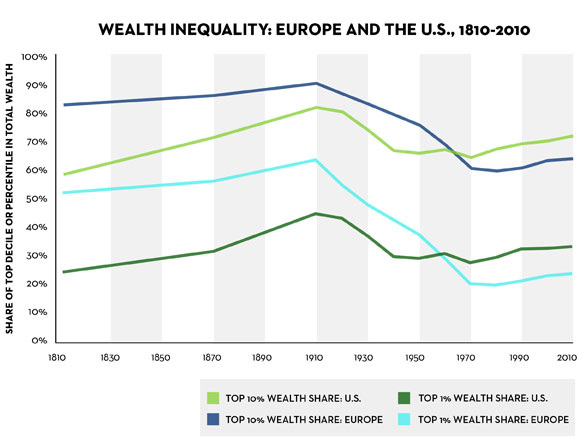

The first is that the entire book is a warning, based on newly accumulated data and Piketty's own theories, that wealth is becoming as concentrated in the hands of the few as it was just before the mass wealth destruction of the two world wars.

What is a little odd is that Piketty spends hundreds of pages cataloging the similarities between today and the Belle Époque/Gilded Age, and then grimly predicts that we might be headed toward...a new age of "patrimonial capitalism," with wealth inequality rising indefinitely. Not war.

(He actually does mention the possibility that capitalism as currently constituted could lead to a new economic crisis or war "this time truly global," but suggests wealth taxes could forestall that possibility. What's interesting to me is that so few of Piketty's reviewers and fans latched on to this question.)

The other item I noticed was Piketty's brief discussion of the self-understanding of the modern wealthy. Part of his thesis is that today's wealthy are not so different from the heirs and heiresses depicted in the novels of Jane Austen and Honore de Balzac, in terms of how they gained their riches. In terms of self-regard, though, they're nothing alike, he argued. And that goes for the petits rentiers -- the upper-middle class families that are not truly wealthy but have inherited enough monetary and social capital to give their children a leg up on others -- as well as for the plutocrats.

(He actually does mention the possibility that capitalism as currently constituted could lead to a new economic crisis or war "this time truly global," but suggests wealth taxes could forestall that possibility. What's interesting to me is that so few of Piketty's reviewers and fans latched on to this question.)

The other item I noticed was Piketty's brief discussion of the self-understanding of the modern wealthy. Part of his thesis is that today's wealthy are not so different from the heirs and heiresses depicted in the novels of Jane Austen and Honore de Balzac, in terms of how they gained their riches. In terms of self-regard, though, they're nothing alike, he argued. And that goes for the petits rentiers -- the upper-middle class families that are not truly wealthy but have inherited enough monetary and social capital to give their children a leg up on others -- as well as for the plutocrats.

It also bears emphasizing that the role of meritocratic beliefs in justifying inequality in modern societies is evident not only at the top of hierarchy (sic) but lower down as well, as an explanation for the disparity between the lower and middle classes. In the late 1980s, Michéle Lamont conducted several hundred in-depth interviews with representatives of the "upper middle class" in the United States and France, not only in large cities such as New York and Paris but also in smaller cities such as Indianapolis and Clermont-Ferrand. She asked about their careers, how they saw their social identity and place in society, and what differentiated them from other social groups and categories. One of the main conclusions of her study was that in both countries, the "educated elite" placed primary emphasis on their personal merit and moral qualities, which they described using terms such as rigor, patience, work, effort, and so on (but also tolerance, kindness, etc.). The heroes and heroines in the novels of Austen and Balzac would never have seen the need to compare their personal qualities to those of their servants (who go unmentioned in their texts).

More:

In contemporary fiction, inequalities between social groups appear almost exclusively in the form of disparities with respect to work, wages, and skills. A society structured by the hierarchy of wealth has been replaced by a society whose structure depends almost entirely on the hierarchy of labor and human capital. It is striking, for example, that many recent American TV series feature heroes and heroines laden with degrees and high-level skills, whether to cure serious maladies (House), solve mysterious crimes (Bones), or even to preside over the United States (West Wing (sic)). The writers apparently believe that it is best to have several doctorates or even a Nobel Prize. It is not unreasonable to interpret any number of such series as offering a hymn to a just inequality, based on merit, education, and the social utility of elites.

...any character who lives on wealth accumulated in the past is normally depicted in a negative light, if not frankly denounced, whereas such a life is perfectly natural in Austen and Balzac and necessary if there are to be any true feelings among the characters.

Piketty goes on to explain that he doesn't think society has become more meritocratic. It may have transformed from one of a very few rentiers with vast inheritances to one of a larger number of petits rentiers, but the aggregate influence of inheritance or birthright is still the same, in financial terms at least.

Piketty is obviously left-wing, but this strikes me as one of the more right-wing ideas in the book. The subtle implication is that today's petits rentiers are different from the aristocrats of the olden days in degree but not kind -- but without the honesty about the advantages they enjoy in life.

In other words, the big difference between Fitzwilliam Darcy and his modern counterpart is that Darcy was supposed to feel a sense of nobless oblige.

Piketty is obviously left-wing, but this strikes me as one of the more right-wing ideas in the book. The subtle implication is that today's petits rentiers are different from the aristocrats of the olden days in degree but not kind -- but without the honesty about the advantages they enjoy in life.

In other words, the big difference between Fitzwilliam Darcy and his modern counterpart is that Darcy was supposed to feel a sense of nobless oblige.